Last Updated on July 14, 2024 by FANGORIA Staff

In February, this column is getting weird. As much as the fire hose of horror soundtrack releases offers an opportunity to celebrate classic composers, scores and films, it also introduces fans of the genre and collectors of media to obscurities they may never have heard or seen, and to artists to whom it behooves them to pay attention. But film music exists in many forms — sometimes as moody boilerplate, others for stories unfolding in the imagination — and it’s these outliers that we’re focusing on this month. These titles may or may not be as obviously or immediately appealing, but they’re a part of the same tapestry as the titles covered in the past, and more importantly, they’re great in their own right. So check out what’s new, and before you know it, you may broaden your horizons just a bit. (And don’t worry, we snuck in a couple of items that are more conventionally exciting as well.)

Antoni Maiovvi is the cofounder of Giallo Disco, a record label whose name should alert you to the sound of its releases before you even hear them, as well as the composer of a number of short and independent horror film scores, including Yellow, released by Death Waltz in 2013, Cuckoo, Housewife and more. He’s cultivated a real expertise both at finding ways to create creepy vibes on a dancefloor (his Mater Proditus EP is a real sizzler) and to develop melodies that ooze with atmosphere (the 2014 live “re-score” of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre he created with cult musician and fellow composer Umberto is a deeply unsettling masterpiece that works even without accompanying Tobe Hooper’s visuals). Though the pandemic prompted him to take a day job teaching studio recording, Maiovvi just released his latest effort, In Private, on a limited-edition cassette through Redscroll Records, a label local to his current home in Connecticut.

In Private is far from the first album to be conceived (intentional or not) as the soundtrack to a film that hasn’t been made. But Maiovvi maximizes the opportunity to tell a story with his music, sequencing tracks to create a narrative that the listener can see in their mind, from the ominous “The Crash That Took An Entire Generation Away” to the menacing “The Sewers Spit Out Their Corpses.” It’s a sizzle reel for jobs he hasn’t yet been given, but definitely deserves. Leap-frogging between synthesizer-heavy tracks that would sound perfectly at home on Sinoia Caves’ Beyond the Black Rainbow or Disasterpeace’s It Follows scores and more mournful string-driven pieces, he exudes a versatility that elevates and distinguishes his work from other musicians and composers working in the same niche. In Private has only one (minor) shortcoming — you need a cassette player to listen to it — but it’s more than worth the effort to dig out an old Walkman and a pair of headphones.

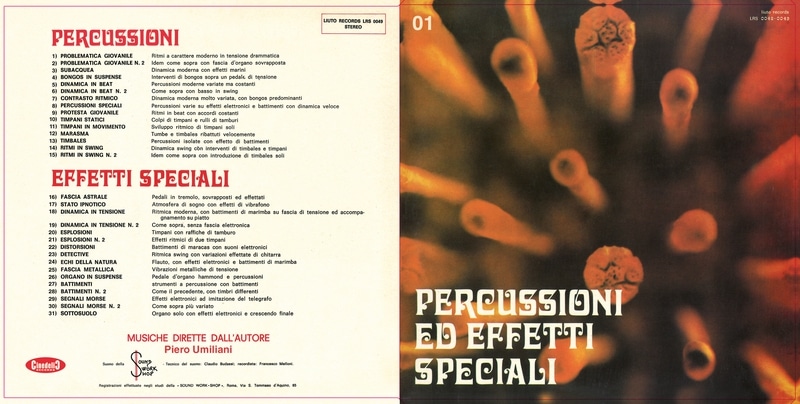

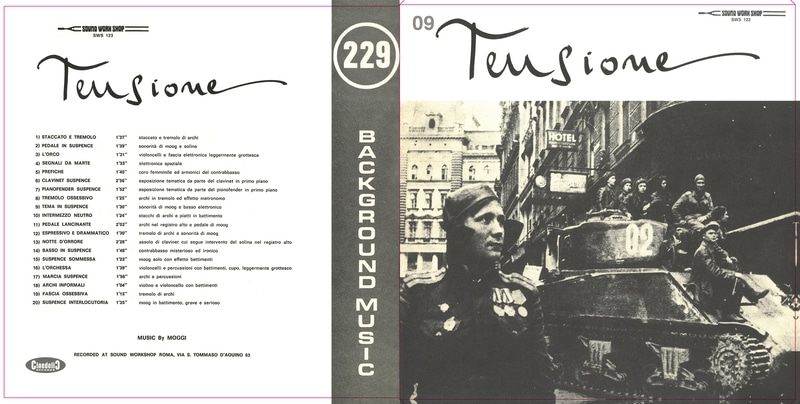

While Maiovvi’s music plays for a film that doesn’t exist, library music is a genre unto itself that fills in score and soundtrack for one without the time, resources, or inclination to create something original. Probably the most famous use of library music in horror history is George Romero’s licensing of it for Dawn of the Dead, but even if Juan Piquer Simón’s Pieces actually utilizes cues from movies scored by Stelvio Cipriani, Carlo Maria Cordio and more, the fact that the film credits “Cam,” a record label and not a composer for the film’s music tells you that he bought them from a music library. Italian composer Piero Umiliani was best known for his action and erotic scores in the 1960s and ’70s, but like Ennio Morricone, Nico Fidenco and many of his other contemporaries, recording library music offered a stopgap between films; and while much of this material (from all of them) is either not properly archived or lost altogether, Cinedelic Records just released an extraordinary CD box set titled Library Music – Volume 1 collecting 13 full albums of Umiliani’s work in the genre.

Strictly speaking, it’s probably inaccurate to call library music a genre; it’s actually a category containing many genres, and while there were records that covered a lot of different bases, many of them were all created around a theme, from horror to comedy to romance, that filmmakers could choose from for scenes in their work. Umiliani’s music here starts with “Percussion and Special Effects” and wraps with “Electronic Suspense,” and in between, there’s “Restless World,” “Cheerful and Relaxing Motifs,” and much more. The 13 albums were released between 1972 and 1983, and without being any particular sort of progression, they offer a fascinating journey for a listener to take; from the “Percussion” side of Disc 1, “Percussion and Special Effects,” “Protesta Giovanile” chugs along like a go-go dancer’s theme song, while on the “Special Effects” side “Detective” swings with jazzy urgency. On Disc 2, “Underground,” the first track, “Flying” rocks with psychedelic energy; and then “Passeggiata” on Disc 3, “Rhythms and Dynamic Themes,” settles into a funky summertime groove.

Suffice it to say, each disc has its own energy, but Cinedelic’s careful, comprehensive treatment lets the listener choose the vibe that they want (and offers plenty of unique and different options). Disc 4, “New Romantic Arias,” flows from one sweetly melodic track to the next with an effortlessness that turns it into beautiful background music, while Disc 5, “Musica Classica Per L’uomo D’oggi,” straddles some traditional classical musical structures while using then-contemporaneous instruments, injecting synthesizers like daggers into baroque compositions. Admittedly, the disco on Disc 8, “Discomania,” does not quite live up to the heights of the genre (especially for 1978, the year in which this record was originally released), but what its wah-wah guitars, bongos, and lilting strings remind you is that this was meant to be a placeholder or replacement for the pop songs a project couldn’t actually afford, and as a result, they become intriguing approximations or also-rans of songs that you actually would have liked or listened to during that era.

Disc 9, “Tensione,” which translates to “voltage,” features some more traditional cues of shrieking strings, but it also contains ones like “Pedale in Suspence,” where Umiliani juxtaposes those organic elements with more idiosyncratic and electronic instruments that bridge an artistic gap between the sounds of exploitation and b-movies in the ’50s and ’60s and that of those genres in the 1980s when filmmakers could enlist composers with a skill set on the then-new digital equipment that artists like John Carpenter, Fabio Frizzi and others turned into horror movie manna. By itself, Library Music – Volume 1 is not only a full musical meal, but a really exciting and surprising education for folks unfamiliar with library music that’s also extremely fun to listen to.

If you haven’t yet wandered off from this Quentin Tarantino-OCD-party conversation crash course in film music’s oddities and digressions, rest easy knowing that the last of this month’s selections come from a real movie — and a bona fide classic at that. As always, Waxwork Records releases some of the best-produced soundtracks from the horror genre’s top films, and its premier release of 2022 is Pino Donaggio’s music for Brian De Palma’s Carrie. Looking back at it, this score is essentially a dialectic between the romanticism of late ’60s and early ’70s horror composers like Morricone and Riz Ortolani and the emphatic suspense of the scores from ’70s “prestige” (read: studio bankrolled) films like The Exorcist, The Omen and The Amityville Horror, where luminaries like Jerry Goldsmith and Lalo Schifrin offered their riffs on Bernard Herrman’s music for the shower scene from Psycho. Some of it’s too pretty for horror, and some of it’s too simplistic for it (especially in 1976), but together it operates in the same referential way that De Palma’s films do, for a simultaneously visceral and almost nostalgic effect.

Donaggio also composed a few goofier cues like “Calisthenics” or the halfhearted disco of “The Tuxedo Shop” that break up the sweet-scary rhythms of the rest of the score in a welcome way. Still, it’s ones like “Carrie and Miss Collins” that so unforgettably underscore Carrie White’s tragic, alienated journey, while “The Coronation / The Blood” is so vivid and operatic that you can see every swing of the camera as it follows that rope up to the rafters where a bucket of pig’s blood waits to rain down on Carrie, unleashing the full intensity of her powers during the film’s climax. Finally, some extra fake pop tune cues conclude the record. Versions of library music recorded deliberately as background or “source” music played not over the scene but inside them, whose AM-radio vibes manage to lull you into a state of calm and vulnerability that’s unexpectedly, thrillingly broken by the brilliance of Donaggio’s mastery of melody and mood. Of course, De Palma’s film operates the exact same way, even before Carrie’s hand juts out from beneath the rocks on her grave to grab Sue Snell; but the score for Carrie is a bit of an overshadowed classic, and like the other records listed here, revisiting or focusing more intensely on it offers multiple rewards.